As with other bonds, municipal bonds are loans made by the bondholder to the issuer that are paid back at a specific time. These bonds pay a rate of interest that is specifically outlined in the bond. Maturities, or the payback time, of municipal bonds vary between one and 30 years. There are also floating-rate and zero coupon municipal bonds that are more complicated structures for bond rates.

Municipal bonds also commonly include provisions. These provisions can add insurance to the bond in order to reduce credit risk and sometimes include the right to “put”, or sell back the bond to the issuer at par value at a specified date before maturity.

General Obligation Bonds

General obligation bonds, or GO bonds, are backed by the full faith and credit of the issuer. The issuer usually relies upon its ability to raise taxes to reduce its credit risk. For local government this usually means property taxes, while for state governments it means sales and income taxes.

Revenue Bonds

Revenue bonds are issued to support revenue-generating projects. A few common examples of these types of projects are toll roads, sewage systems, bridges, and airports. Revenue bonds reduce credit risk by offering investors a small portion of the revenue generated by these public projects.

Municipal Bond Advantages

A major advantage of municipal bonds is that the revenue stream created by the bond is exempt from state and federal taxes. These bonds are liquid and may trade freely at anytime. Additionally, these bonds are considered low risk because they are backed by the solvency of the state or local government.

Municipal Bond Credit Risks: Government Funding Gaps & Defaults

The value of municipal bonds are backed by their respective state and local governments. If these state and local governments declare bankruptcy, then the bondholders have the potential to lose all of their investment. Historically, a state or local government declaring bankruptcy is rare, but it does happen.

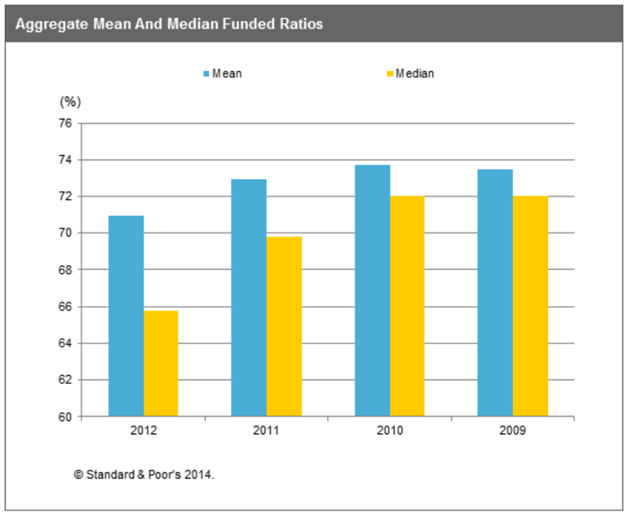

According to a Standard and Poor’s report, average and median state funding ratios have actually decreased since 2009.

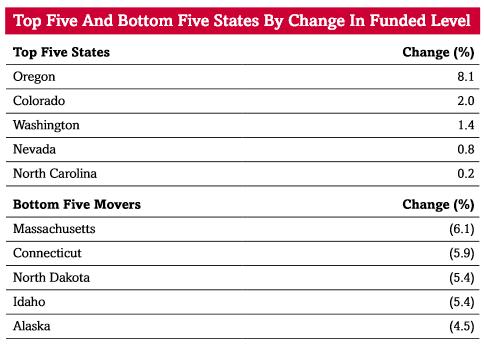

Not all states are equal in the eyes of investors. The less funded a state is, the more likely it is to default. As you can see below, Massachusetts, Connecticut, North Dakota, Idaho and Alaska are having a hard time plugging their funding gaps.

But sometimes municipalities default, and when they do, it gets ugly.

The Great Default of Detroit

The city of Detroit, Michigan filed for bankruptcy in 2013. It was the largest bankruptcy filing in U.S. history, with debts estimated at $20 billion, surpassing Jefferson County, Alabama’s $4 billion filling in 2011.

Detroit’s bankruptcy caused yields on bonds issued by the city to skyrocket to record highs, meaning prices declined to record lows. The yield jumped from 8.39% in mid-May to 16% in mid-June. The default included unlimited general obligation bonds, which were previously thought to be “untouchable” by default.

The major reasons why Detroit had to declare bankruptcy were a shrinking tax base due to population decline, program costs for retirees, borrowing to cover budget deficits, poor record keeping, government corruption and the fact that 47% of homeowners had not paid their property taxes in 2011.

The Bottom Line

Municipal bonds are traditionally very safe investments because they are backed by the credit rating and tax revenues of state and local governments. Further, these investments have significant tax advantages that produce stable income streams and fund important public infrastructure. However, when investing in municipal bonds, be sure to place your money in diversified funds to reduce the risk of default. Also, only invest in the highest-rated debt in order to obtain the maximum safety for your money.

Image courtesy of Pong at FreeDigitalPhotos.net